Today begins a series of eight reflections on the Hours of prayer, starting with Vigils, the time deep in the night known as “the long dark.” This series celebrates the release of the Praying the Hours soundtrack by Lolo Meares. An excerpt from the Vigils album of the soundtrack starts the post so that you can have her portrayal of this dark Hour in your mind as you read. (A link to the Vigils album can be found at the bottom of this essay, along with a link to the book Praying the Hours in Ordinary Life from which the essay is taken.)

The moon is overhead, the Watchman waits.

Vigils is the night hour, the longest hour, the polar opposite of Sext at noon. Like the noon hour, the light source is overhead: but at midnight, the moon casts strange and sharp shadows that give the illusion of life to inanimate but familiar objects, redrawn by the darkness into threatening figures. Things happen at this hour that do not happen at any other time, lost souls wander, harm is plotted. The Vigils hours bridge the gap between sleep and sunrise, a dark purgatory where evildoer and intercessor alike find purpose. In the worship of false lords, the 3 a.m. hour is called the witching hour, a mockery of the time at three p.m. when Christ died. Vigils contains the drama of both righteousness and evil.

The Latin root of the word vigil means “wakefulness.” To keep Vigils does not mean simply to be unable to rest, to be anxious or beleaguered by mind-revving sleeplessness. Keeping Vigils is rather to be purposefully awake at a time when one would otherwise (or surely rather) sleep. This element of intention to wakefulness is why “vigil” is also applied to some traditional devotional observances. In Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic traditions—as well as in many cultures—a vigil is sometimes held during the dark night when someone is gravely ill or dying, and can extend through to burial. In some ancient and often primitive cultures, this ritual had the practical application of protecting the body of a loved one from harm until buried “safely”—deep enough to be beyond violation by enemy, spirit, or animal.

Vigils is a time for prayers that are solitary, languid with long hours, yet with the qui vive of a sentinel. The beautiful but heartbreaking description of sorrow found in Lamentations 3 is Jeremiah’s consummate Vigils prayer, ending with: “My soul continually thinks of it and is bowed down within me. But this I call to mind, and therefore I have hope: The steadfast love of the Lord never ceases, his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness. ‘The Lord is my portion,’ says my soul, ‘therefore I will hope in him” (3:20–24).

The night watch is a boundaried wakefulness; to kill or waste time is to fail the watch and to ignore the nature of the kairos time in which it takes place. To remain awake and prayerful at Vigils, then, is a practiced discipline, but like the prophet Jeremiah’s deep-night reflections, it is often an hour of melancholy and yearning for dawn: “my soul waits for the Lord more than those who watch for the morning, more than those who watch for the morning” (Psalm 130:6). The watchman, one is tempted to imagine, is thoughtful, grim, and made otherworldly himself by his duties.

The dark and the light are the same to God, the psalmist tells us. Silence is the soundtrack of this Hour, whispers and listening, mystery, danger, trust. The purpose of this time is to learn to trust God in the darkness. On the façade of the National Cathedral in Washington D.C. there is a statue of the archangel Michael keeping the night vigil. When the sun rises, it finds him with his sword finally lowered, because his watch is over at first light. Above the archangel is a gargoyle covering his ears and screaming at the sound of the trumpet blast of Lauds.

Ich bete wieder, du Erlauchter

Once again, I pray, your Majesty.

Once again, you hear me talk in the wind.

From my innermost being never-used words

gush forth in a mighty way.

I was confused:

my ego fractured, every piece of me was turned over to the enemy.

Oh God, the scornful scorned me, and drunks reveled in my misery.

I crept into people’s back yards,

ate out of garbage cans and collected broken glass.

With my half-opened mouth I stammered

at You, who are full of grace.

I raised my tired hands to You, in nameless pleading,

that I would find my eyes again, with which I once beheld You.

I was a house, ruined by fire, where only murderers seek to rest

’til relentless law dogs them to a further place.

I was like a city, built by the sea, afflicted by a plague

that clings heavily, like a corpse, to the hands of children.

I was a stranger to myself.

Her broken heart pulsated her pain to me, in her womb.

But now, I am restored, assembled from pieces of my shameful past.

I yearn for Your holy covenant, for Your all-consuming wisdom

to preside over me.

I yearn for the magnificent hands of Your generous heart.

Oh, come closer.

Here is what counts—only my God and me,

and You have the right to squander me.

—Rainer Maria Rilke, The Book of Hours, II, 2

translated by Martina Nagel

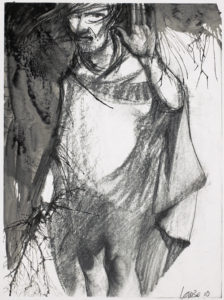

Denise Louise Klitsie’s angel of vigils keeps watch in the dark (illustration from Praying the Hours in Ordinary Life)

Excerpt on Vigils from Praying the Hours in Ordinary Life by Lauralee Farrer and Clayton J. Schmit, Wipf and Stock, 2010, used with permission and found here. Excerpt from the album on Vigils, from the Praying the Hours soundtrack by Lolo Meares—with artwork by Lori Fox—can be freely streamed or purchased here.

*This Just In: Thank you Eric and Jon & Marianne: your gifts were timely—both in their financial provision and their encouragement. Nice radar, as always. (If you want to see the film or receive updates, write to info@burningheartproductions.com. To contribute to its release, go here.)