by Patrick O’Neil Duff, editor

Today I turn 32 years old. My life consists of daily interaction with my two-year-old daughter, my four-year-old son, and fifty-some-odd college students. In other words, I live in a cesspool of unwashed hands and runny noses, surrounded by individuals who don’t know how to keep themselves healthy. For the past month, I have been swapping various pathogens with little prospect of health, and right now, I am sick. Worn down and stretched thin. And it’s my birthday.

Last night, with a great sense of weary contentment, I finished a rough cut of the Praying the Hours segment of “None.” I wanted to take a moment and share my experience.

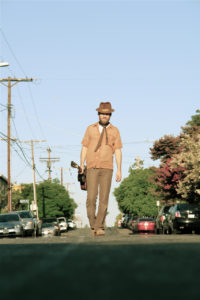

“None” tells the story of a musician whose musical career and ambitions have dwindled and who lives within a tension of competing hopes and dreams, a reality in which much is desired and little is fulfilled. A business owner and family man, he has little time to devote to anything outside obligation, and often even obligations fall to the wayside. Though the possibility of a career in music has darkened as a possible horizon for None, it is still the place he finds expression, beauty, sadness, solace, and regret. His life is not a daily grind of gears—the gears have become so worn down that they spin aimlessly, no longer even able to achieve any desired purpose. None’s spark is all but used up; but then old friends return, and a chance to rekindle that spark of long-abandoned dreams is realized.

I borrow shamelessly from G.K. Chesterton in the following thoughts on kairos and chronos time—a concept at the core of the Praying the Hours project. In his book Orthodoxy, Chesterton writes:

As we have taken the circle as the symbol of reason and madness, we may very well take the cross as the symbol of mystery and of health. Buddhism is centripetal, but Christianity is centrifugal: it breaks out. For the circle is perfect and infinite in its nature; but it is fixed for ever in its size; it can never be larger or smaller. But the cross, though it has at its heart a collision and a contradiction, can extend its four arms for ever without altering its shape. Because it has a paradox at its centre it can grow without changing. The circle returns upon itself and is bound. The cross opens its arms to the four winds; it is a signpost for free travelers.

Chronos is a circle; it seeks to keep everything bound and under control. Kairos is a cross, a collision and a contradiction; it is something unleashed and released. Kairos breaks into chronos, the extraordinary into the ordinary, the sacred into the profane, the infinite into the finite. It is the Incarnation of God as Jesus the Christ, it is Paul the Apostle’s experience on the road to Damascus, it is the still small voice and the “strange warming of the heart,” that John Wesley described as the believer’s experience.

Every story in Praying the Hours has this kairos collision. For me, this moment happens in “None” in the final scene, as None stands at the back of a crowd, watching his friends play music, contemplating a paradox of weariness and contentment: “I see that nothing lasts forever. I can make peace with that. But I still feel alone.”

Every story in Praying the Hours has this kairos collision. For me, this moment happens in “None” in the final scene, as None stands at the back of a crowd, watching his friends play music, contemplating a paradox of weariness and contentment: “I see that nothing lasts forever. I can make peace with that. But I still feel alone.”

As I have spent time with this edit, I realize that None and I are kindred spirits. At one time, my dream was to work in the film industry. This dream faded as my prospects to fulfill it fell away one by one, and other things in my life filled the void. Other passions and talents were revealed to me: I love to teach, I love being a husband and a father. However, in this process, I gave up my creative dreams when I felt drawn to attend Fuller Seminary, a graduate institution for the study of theology. I became active in leadership at my church. I started investing in people, family, students, and I gave up on any notion of making movies. Since I started seminary in 2007, I hadn’t worked on a single creative project.

And then my kairos moment happened. Director Lauralee Farrer asked me to be involved with Praying the Hours, and at first, I told her “no.” How could I commit to anything more with so much going on in my life—family, work, school, church? It was my wife, Sarah, who gave me a firm shove in the project’s direction. Break free.

Film editing was something I had given up on. I had let it go. Mourned its loss. Moved on. And then I believe God gave me something I had buried and forgotten. God gave editing back to me. A mind-blowingly amazing, undeserved, unexpected gift. And I am devastatingly thankful and humbled.

I am weary, yet content. I am officially a year further in this journey. If kairos is indeed a signpost for free travelers, as Chesterton posits, we must have our heads up as we walk, ever looking around for these signposts which light the way.