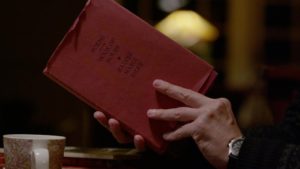

The Traveling Man (Christopher Min) holds a book of poetry by Rainer Maria Rilke on the Hours of prayer—one of the inspirations behind the movie.

We called the completion of Praying the Hours a little over two months ago—on Mayday, 2021, so it would be easy to remember. Within the time since then, while I have been working on finding its audiences, I picked up one of my journals from over two decades ago. There I found the slip of an idea that became, as it was recently called on a form, a “three-hour epic narrative feature.” It surprises me to read that, and I’m the one who made it.

A little over twenty years ago, discovering the spiritual discipline of praying the hours was so revolutionary to me that it changed the way I view the world. (If you’re interested in more on the basics of praying the divine office, write to me at info@burningheartproductions.com and I will send you a copy of my book Praying the Hours in Ordinary Life.) It’s a good thing: my worldview needed revolutionizing. I have never felt particularly evangelistic about that experience—it’s not my goal to have others repeat or validate it. But while I was reflecting on this life-altering event, I had an idea that intrigued me enough to record it in my journal, where it was content to live for several years without disrupting my life at all.

And then one day I woke up and found that idea sitting in my living room, feet up on the coffee table, eating my breakfast. It followed me everywhere, pointing out the ways it was embodied no matter where I looked. “All you have to do is start filming!” it said. I wrote it as a treatment (a story on which a film is based) for a 40-minute short film, just to get it off my back. Then that treatment started groaning for lack of space, complaining that the box it was in was too small. It became something I found myself writing about when I was supposed to be writing other things. I talked to my (then) Burning Heart Productions producing partner Tamara Johnston, who was intrigued, and her boyfriend, (and my heart-son) Matthew, who wouldn’t shut up about it. “Let’s do it,” he kept saying. “When are we going to start shooting Praying the Hours?” Slowly, while I wasn’t paying attention, the treatment turned into a feature script.

Suddenly, lots of people got interested, lots of folks (it seemed) wanted a piece of it. Lots of time went by, money and energy and a lot of flurry was expended—and nothing happened. The script pressured me to be made but I was unable to bring it to life: I lacked the skill, the circumstances did not cooperate, but mostly I didn’t understand what kind of movie it wanted to be. Movie stars were intrigued, agents attached, producers gushed over the script, saying it was so good that they recommended bringing in more experienced screenwriters and directors (sigh). In the same weekend I had one producer say it was the best script he’d ever read and another say it was the worst: “un-produceable.” I was told that funding was close so often I didn’t bother to yawn when I heard it anymore. Then Matthew was killed.

Suddenly, the nature of time became clearer. I brought a team of people together and we started filming (on 35mm). It was complicated. We were grieving. That weekend cost $35,000, which I paid each person in installments over two years. As it turned out, a problem with the camera resulted in the footage being out of focus, unusable, but my vision was slowly clearing.

The story—and those expensive rolls of exposed short ends—sat on a shelf, humming with impatience for years. I had explained it to so many people that everyone asked about it, to my increasing chagrin. Whatever happened to that movie you were going to make about the prayer thing. It tormented me, like a bad breakup that people wanted the details on. We made a second film, a feature doc. We made a third feature, and still Praying the Hours sat on a top shelf, complaining to be made like a smoke alarm needing a replacement battery. Tamara and I both took j-o-b-s to pay our rents and I tried to imagine making films with only the resources available to me. I gave speeches on panels about using your cell phone if you have to, “just make your films!” I urged younger filmmakers. Hypocrite.

Along the way I saw that the window of opportunity to make the story never closed because it was always pertinent. I saw how it moved with me from context to context, remained a good idea, retained verisimilitude, that is, it continued to be true no matter how my context changed. I realized that I could apply the story at any point in my life when I was ready to do it, because the story would always be right there in the people before me, no matter who they were, always true. That was something rare.

I felt forced to come to one of two conflicting conclusions: that it was not necessary to embody the Hours of prayer because that has already been done perfectly in creation. The other was a moral imperative: because I had been shown my world in a new light, I needed to capture that as honestly I could. I chose the latter, believing that something new might be known that might not otherwise be known. Like van Gogh’s old boots, like Monet’s haystacks, Kahlo’s self-portraits: what is the moment when an artist feels an obligation to capture what she has seen, not as a piece of propaganda or a manifesto, but in obedience to an original inspiration? Arthur Miller once said something about characters that also works for artists—we are defined by the kinds of challenges we can’t walk away from and by those we’ve walked away from that cause us remorse. On May 1 of 2021, I shed the burden of remorse.

For the majority of the time that I put my creative energy and my disposable income (and the support of my friends) into pushing this project from idea to feature, it has been an act of obedience as much as anything else. People ask, quite to my surprise, if it is my magnum opus. No. It is the most extreme idea, the most dogged work, and without question a marathon. It’s likely I will not live long enough for any other work to compete with the years this has taken to come to fruition. But to call it my magnum opus gives me too much credit—it did not feel like it was “mine” from the beginning. The idea came from someplace outside of me and insisted itself into existence. I just gave in. —Lauralee Farrer, Director

*This Just In: Thank you Karla and Joanna for your contributions to the long road of making Praying the Hours and now, finally, its slow burn of a release. Thank you for all your contributions, sisters, of talent and love and courage-giving. (If you want to see the film or receive updates, write to info@burningheartproductions.com. To contribute to its release, go here.)